As part of our celebrations for World Alzheimer's Month 2015, or Dementia Awareness Month as we have been calling it, we are proud to publish an excerpt from a chapter in a book, written by one of our members in the UK, Professor Peter Mittler.

As part of our celebrations for World Alzheimer's Month 2015, or Dementia Awareness Month as we have been calling it, we are proud to publish an excerpt from a chapter in a book, written by one of our members in the UK, Professor Peter Mittler.

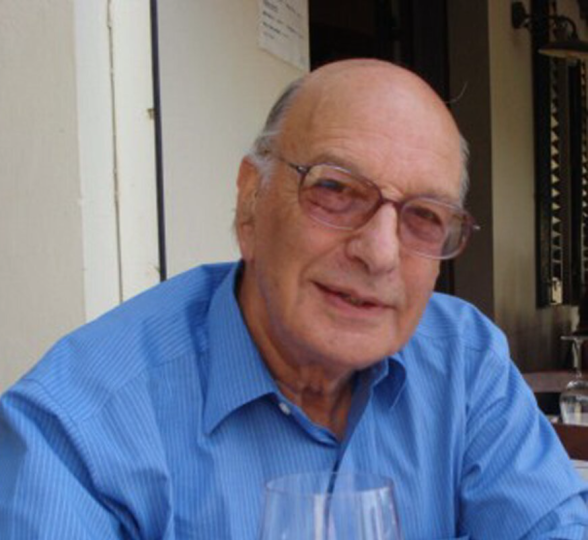

Peter Mittler is Emeritus Professor of Special Needs Education at the University of Manchester. He trained as a clinical psychologist, and devoted his career to championing the rights of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities to education and citizenship. He is a former President of Inclusion International, a UN consultant on disability and education and is active in promoting the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

He was diagnosed with ‘early, very mild Alzheimer’s’ in 2006, and the article which follows is an updated and revised version of an invited editorial which first appeared under the same title in the journal Dementia [i].

JOURNEY INTO ALZHEIMERLAND

In Whitman, L. (ed) People with Dementia Speak Out. London: Jessicca Kinglsey Publishers. 2015

Then

I would probably not have asked for a referral to the local memory clinic if I had not had previous experience of assessing people for dementia in my first job as an NHS clinical psychologist. I remember my discomfort at that time in realising that test findings did not necessarily reflect what people could or could not do in real life situations. That lesson is now part of my own story.

I went to the clinic because my wife and I were concerned about an increasing number of memory lapses, such as not bringing home the right shopping and forgetting to do routine things like switching off lights and closing cupboard doors. I knew that early diagnosis was important and that drugs were now available which could at least slow down the deterioration associated with the disease.

The experience of being on the ‘other side of the table’ at the age of 76 was a bit strange at first, especially when I realised that I had used some of the same memory tests 50 years earlier. My psychological test results showed average or above average functioning in most areas, with the significant exception of tasks involving immediate recall of strings of unrelated words or pictures. I half expected this finding, because when my children were small they could always beat me at games requiring the recall of large numbers of upturned pictures, but a series of brain scans also revealed a greater degree of cortical atrophy (‘holes in the head’) than might be expected at my age. After reviewing all the evidence, including a detailed account of the concerns expressed by my wife, the consultant told us that although Alzheimer’s could only be fully confirmed at autopsy, the balance of probability lay with a diagnosis of “early, very mild Alzheimer’s Disease”. I trusted his experience, politely declined his offer of a second opinion and arranged to donate what was left of my brain to the Brain Bank research programme.

When I first told people about my diagnosis, most were incredulous, dismissing examples of my memory lapses as mere ‘senior moments’ and capping them with more serious examples from their own experience. However, the fact that I do not display ‘obvious’ symptoms of dementia does not mean that the diagnosis is wrong – that I am a ‘false positive’, in the medical jargon.

Now

The good news is that eight years later, the rapid deterioration which I was expecting has not materialised. My psychological test results have not changed over many re-assessments: in fact, the most recent reflects a slight improvement on the first. Even the tests of immediate recall on which I feel I do very badly are now just within the average range for my age.

My day to day functioning in most areas seems to me to be about normal for my age and background. I still sometimes forget to shut drawers or put things back where they belong but claim to get it right more often than not. I can look after myself if necessary and undertake complex journeys. I feel reasonably competent in driving in familiar areas but am now more watchful and slower at decision making and worried about the annual renewal of my licence.

In many ways, my intellectual and cultural horizons have expanded since I retired from full-time university work 20 years ago. My reading has been enriched to include twentieth century history and politics, as well as travel books and modern literature and I now have a fuller appreciation of music and the visual arts, especially since acquiring a second home in Florence. I have published a memoir and contributed several new papers to academic and professional journals on the implementation of the new United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities which could greatly improve the quality of life and support for all disabled people, including those living with dementia[iv]. Nevertheless, I have decided to stop academic writing because I now find it more difficult and because it takes up too much time which can be better spent in more rewarding activities.

An A* in GCSE Italian in 2008 provided welcome independent evidence that I could still learn, while the high marks that I later received for an Open University degree level module in Italian did more for my self-esteem than my doctorate several decades earlier. Despite my good examination marks and competence in reading and speaking Italian, my ability to understand and follow a conversation is disproportionately low, even under ideal acoustic conditions when I am wearing headphones to listen to a studio-recorded disc. This could be due to Alzheimer’s, old age, or some complex combination of the two. Be that as it may, it is frustrating for me and confusing for Italians who assume that because I can speak the language, they can talk at their normal speed – and all at once.

It is difficult to draw a clear line between the effects of ‘normal ageing’ and Alzheimer’s disease for people at my end of the dementia spectrum. The difficulty is overshadowed in my case by severe deafness which now deprives me of some 70 per cent of normal hearing. My particular combination of dementia and deafness is more than doubly debilitating because it affects the quality of my life and relationships. Although digital hearing aids can amplify sound, they are not yet able to strike a balance between essential foreground information and background noise in social situations and restaurants. Irrelevant and intrusive music makes it particularly difficult for me to follow a story line on radio or television, though I can still do so in reading. It is also difficult for me to use the telephone because although I may be able to hear the speaker, it takes me much longer to understand what is being said. Worst of all, even one-to one conversations in quiet conditions can become frustrating because I have misheard or misunderstood what has been said when I thought I had been listening hard to avoid communication breakdowns. These ‘processing difficulties’ are associated with dementia but there is very little knowledge or understanding about their impact on people who also have a significant hearing loss.

Nevertheless, there are times when dementia does seem to be the most likely explanation of behaviours which are completely out of character. One notable example occurred in Italy several years ago when I forgot to move our car from the town square before market day, only to come across it the next morning surrounded by fruit and vegetable stalls and with a policeman bearing down on me, notebook in hand. I had always remembered to move the car in good time, so this lapse was quite uncharacteristic. Furthermore, I had already spent some time in another part of the market that morning without anything triggering a reminder that I should have moved the car on the previous evening.

These episodes are mercifully rare, and I do what I can to prevent them by making a list of day to day tasks. But there are times when a new mistake makes me wonder whether the deterioration slope is about to become steeper, even precipitous, as happened with a friend of ours. Examples include the misreading of a timetable which caused us to arrive at a railway station an hour too early and another day when I made five small mistakes, each of which could be mistaken for ‘professorial absent-mindedness’ but which, taken together, might be the first sign of a more rapid decline.

Next?

Like autism, dementia is on a spectrum. I am fortunate to be at one end of that spectrum but how long can this continue? Annual health checks show that apart from hearing, all my other systems are functioning well for my age but how long will my addled brain be able to keep pace as I go through the second half of my 80s or 90s? When I put this question to my consultant after four years, I was encouraged by his statement that there was no reason why the next four years should be any different. I was sceptical about this prediction but relieved that it seems to have been confirmed.

Although I am now more interested in prognosis than diagnosis, I later asked him if he had considered the alternative classification of ‘mild cognitive impairment’ which was by that time beginning to be more widely used. I also asked him to imagine a scenario in which he is acting as an expert witness on my behalf in a court of law where I am on a serious criminal charge. What evidence would he use to support his diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease against another expert witness who insisted that I was within normal limits for my age and therefore fully responsible for my actions? After reviewing my tests and brain scans, he stood by his diagnosis, adding that I had “plenty of reserves in my spare tank” and that the medication which I have been taking deserves some credit for the absence of deterioration.

What about the next four years? Time will tell.

References:

[i] Mittler, P. (2011) Editorial - Journey into Alzheimerland. Dementia: the international journal of social research and practice, 10, 2: 145-147 reproduced by kind permission of the editor and Sage Publications.

[ii] Mittler, P. (2010). Thinking Globally Acting Locally: A Personal Journey. Authorhouse and Amazon. www.mittlermemoir.com

[iii] Mittler, P. (2013) Overcoming Exclusion: Social justice through Education. London: Routledge World Library of Educationalists.

[iv] Mittler, P. (2015) The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Implementing a Paradigm Shift. In Iriarte, E., McConkey, R. & Gilligan, R. (eds.) Disability in a Global Age: A Human Rights Based Approach. London: Palgrave MacMillan (in press, available from author).