Our blog today published in our continuing daily series for World Alzheimer's Month 2016 #WAM2016 #DAM2016 has been generously written by Meredith Gardner, who is an occupational therapist working within the Gold Coast Hospitals & Health Service.

Our blog today published in our continuing daily series for World Alzheimer's Month 2016 #WAM2016 #DAM2016 has been generously written by Meredith Gardner, who is an occupational therapist working within the Gold Coast Hospitals & Health Service.

Meredith has a special interest in working with people with dementia and cognitive impairments, and enabling people to engage in everyday life and valued activities. Thank you Meredith, we truly appreciate your generous effort to write this article in support of our growing community.

The value of an occupational therapist for people with dementia

By Meredith Gardner

Doing as much as I can: How can we support people with dementia to be independent and engage in meaningful activity?

Participating in normal activities of daily living contributes hugely to quality of life – choosing an outfit, playing with the dog, talking to a friend on the phone, going out for coffee, watering the garden, cooking your partner a meal. These are the things we take for granted until we can’t do them anymore.

We all feel better when we feel like we’re contributing, doing something positive or productive. When we are a part of something bigger than ourselves.

Research shows us that it’s so important to keep using our brains and body in new ways as we get older, to keep neurons firing and muscles activated. Our brains are very crafty, and when brain damage causes difficulty using our brains in our usual way, often our brains create new pathways to get the job done.

Being engaged in activities that we want to do or need to do can provide a sense of identity, competence, joy, comfort, self-expression and improve mood. An occupational therapist assesses a person’s strengths and limitations to enable independence and participation. This is an occupational therapists’ approach to supporting people to do as much as they can.

- Know the person

Find out what’s important to the person with dementia by asking about previous and current life roles, values and liked/disliked activities. Look for activities that validate the person’s sense of identity.

By identifying strengths you can capitalise on those. Strengths could include physical fitness, a social nature, willingness to help or habitual skills.

Sensory impairments, such as hearing loss, visual impairment or difficulty processing sensory information encountered in everyday life can compound problems faced by people with dementia and are a normal part of the ageing process.

- Be goal directed

Dementia can lead to multiple problems in everyday life. What’s important to the person and their loved ones? Focus on one or two goals rather than trying to address everything at once. Goals are likely to change over the course of time.

Here’s an example of what a goal might look like. I will take consistently take the correct medication dosages using a pre-packed medication dosette box and an alarm within two weeks.

Make a plan for the future before crisis point. Consider driving, finances, medication, health directives and enduring power of attorney.

- Grade the task

Most people can participate in everyday life in some way, despite significant cognitive impairments.

There is a huge spectrum between being independent and not being able to do a task at all. We can grade the difficulty of the task from simple to complex. You may need to use a trial and error approach to find out how much the person can do for themselves. Often the person just needs the time and opportunity to do the task.

To enable independence, do with the person instead of for the person.

This can be the hard for the support person. We want to help. We want to help so much we end up doing things for people.

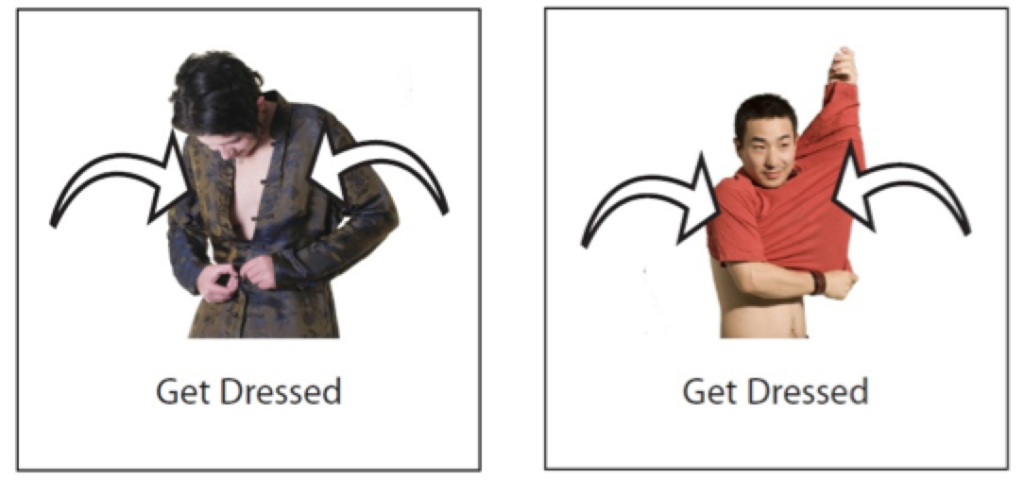

Examples of how tasks can be graded for different abilities.

| Simple | Complex |

| Clapping along to music | Playing the piano |

| Being present while food is cooking, smelling aromas, looking at and touching ingredients | Monitoring food cooking on the stove

Setting the table |

| Sorting socks into pairs | Operating the washing machine |

| Hitting a balloon | Playing tennis |

Types of assistance you could provide:

- Verbal instructions at the start of the task

- Step by step instructions as you go

- Demonstrations

- Visual cues (objects, pictures, signs)

- Backward chaining (you start the task and the person with dementia completes it)

- Forward chaining (the person does the first steps and you complete the task)

- Hand over hand (put your hand over their hand to show the movement)

When grading or modifying a task, it may be to reduce or eliminate a risk. For example, many people with dementia cease driving due to the possibility of a car accident. When considering the risk it’s important to consider the hazard, the potential outcome and the likeliness of that outcome. Some activities like driving will carry much greater risks than others such as not showering everyday day or using a sharp knife. What’s a finger cut in comparison to a life of occupational deprivation?

- Modify the environment

Visual or auditory reminders can help support a cognitive impairment – labels, task checklists, signs, calendars and alarms. I’m already using my smartphone as my back up brain with records of upcoming appointments, contact numbers, shopping lists, tasks which need to be done with specific phone apps designed for this purpose. Other specific technology examples include: a GPS watch (pinpoints location and aid navigation), a medication alarm clock (delivers tablets at dosage time) and a personal alarm (one touch button to family or emergency response).

Given sensory impairments are common in people with dementia, colour contrasting objects can help support low vision. Visual landmarks help people navigate. Remove trip hazards, like small changes in surface height, loose mats or cords.

For people with a lowered stress tolerance or at certain times of day it can be necessary to reduce stimulation to help relaxation and brain recovery following activity. This is as simple as: turning TV/radio off, turning off lights/drawing curtains, sitting in a chair/resting in bed and NOT TALKING! I would also recommend reducing distractions if you need to focus on a more difficult task.

- Habits and routines

Although dementia often affects short-term memory, other memory types can be used. “Procedural memory” is a type of long-term memory, which helps us to do familiar tasks. For example, knowing how to bring a fork to mouth to eat, or how to shave. These motor skills are often unconscious.

When tasks become habit, they become automatic and require less cognition. A regular daily routine can help provide structure, so the person knows what to expect at what time of day. This can reduce the stress of an unstructured day by providing direction for “what’s next”. A visual reminder of the daily routine can be helpful. Try to base the daily routine on the person’s usual routine, for example, if the person is in the habit of showering before bed; make sure this is part of the routine.

Make sure your time frames are realistic – give the person as much time as needed. Being rushed and stressed doesn’t help anyone’s thinking skills. Schedule both physical activity and down time into the down time to maximise function. Routine should be a balance of stimulating (morning) and relaxing (afternoon/night time) activities.

Keep important objects (keys, glasses) in their usual places!

- Trial and error

Problem solving skills are vital in being able to cope with changes in thinking skills and function. When addressing a problem, there are usually a number of solutions. Persistence is key. Be creative! And please share any creative ideas you have with me: [email protected]. Modify your goals if needed.

I just can’t stress enough the importance of doing things to keep your body and brain going! Visiting new places, trying new skills (painting, singing), volunteering, tai chi or yoga.

How to access an occupational therapist:

- People with chronic health conditions can access five free occupational therapy sessions through their GP: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-medicare-allied-health-brochure.htm

- Ask your GP for a referral to adult community health in your area

- People over 65 years can self-refer for an occupational therapy home visit through the Australian governments My Aged Care website: http://www.myagedcare.gov.au or call 1800 200 422.

- Access a private occupational therapists in your area: https://www.otaus.com.au/find-an-occupational-therapist

Helpful resources:

- Independent Living Centre website – almost every bit of equipment you could ever want or need! http://ilcaustralia.org.au

- Tele Cross – free daily telephone call and welfare check from Red Cross http://www.redcross.org.au/telecross.aspx

- At Home With Dementia (NSW Dept ADHC) https://www.adhc.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/file/0011/228746/at_home_with_dementia_web.pdf

- Free council activities (Gold Coast website) http://www.goldcoast.qld.gov.au/community/active-healthy-program-27969.html

- Dementia: Osborne Park Hospital Guidelines for OT in Clinical Practice (WA – DTSC) – specific strategies for certain problems that could arise from day to day http://ilc.com.au/resources/2/0000/0415/dementia_osborne_park_hospital_guide.pdf

- Relate, Motivate, Appreciate: An Introduction to Montessori Activities (Alzheimer’s Australia) https://www.fightdementia.org.au/sites/default/files/AlzheimersAustralia_A5_Montessori_Booklet_WEB(3).pdf

- Allens Cognitive Levels + Caregiver Guides