The reality is that unpaid family carers of loved ones with dementia are often isolated, lonely, exhausted and not given enough information or help to do the job as best as they want.

A friend of Dementia Alliance International (DAI) recently identified a report on an interesting study by University of Queensland researchers which found that found patients who experience delirium are three times more likely to develop dementia.

That report is here.

I've been requested to write an explanatory note about an important workstream in our understanding of dementia. It concerns the influence of something called 'delirium' which I'll explain in this blogpost. It is my pleasure to do so.

Delirium and dementia

Few things touched me emotionally as watching my mum develop dementia at various points, all with an important medical cause or precipitating factor. She was diagnosed with dementia in 2016, and I cared for her until her death in 2022 with the support of paid carers.

Dementia is a chronic illness – but delirium is an acute flare-up. When I was at medical school twenty years ago, it was framed as being ‘reversible’ and innocuous. I think that it is far from that, as it might cause a further acceleration overall in cognitive functional decline once the delirium has settled.

It’s important to treat it if you’re a medic, but it’s equally important for an unpaid family carer to be able to stop it, I think. I’ve now got a seat at the table for carers for a local NHS hospital in London. I need to explain here why I think the subject of delirium superimposed on dementia is so critical to understand.

The practical significance of delirium for people with dementia

As an unpaid family carer, it can be essential to know if your loved one is experiencing an episode of delirium “on top of” an underlying dementia. This is called “delirium superimposed on dementia”.

Whilst dementia is a “slow-burn issue” over months and years, acute episodes of delirium typically last hours or days and are characterised by a very fast and drastic change in personality and behaviour – such as increased agitation or prolonged sleepiness.

Delirium is important. It invariably is a ‘canary in the mineshaft’ – i.e. an external sign that something is going very wrong in the internal machinery of the human body.

For anyone who has witnessed it, it is very emotionally impactful.

Worth reading is this piece on distress in delirium here.

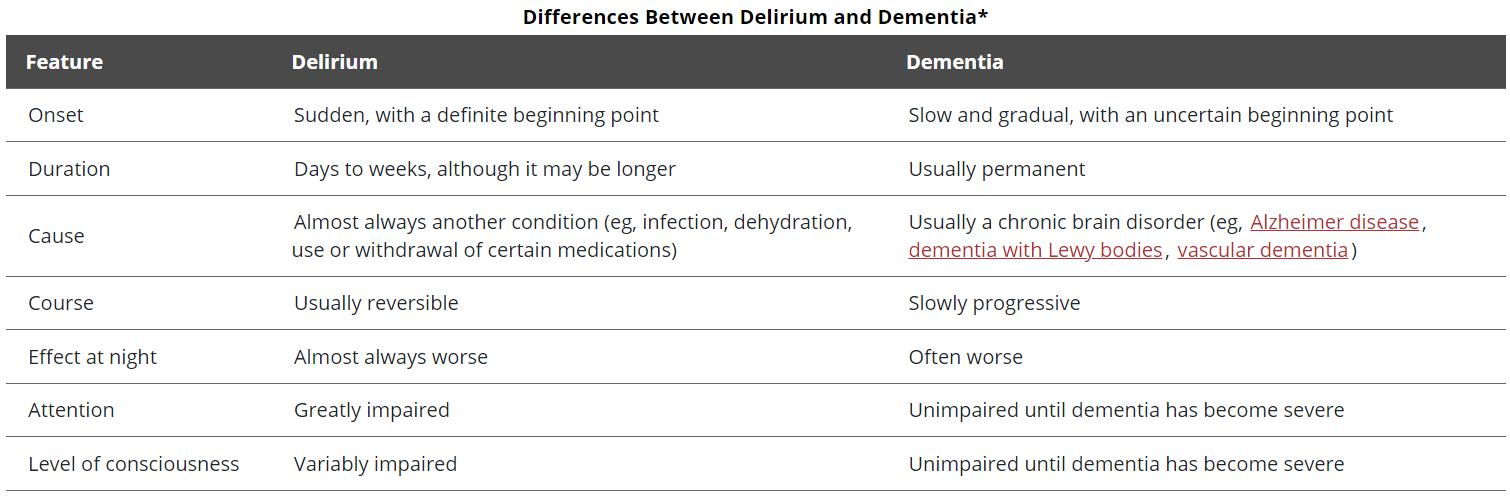

Here are some key differences between delirium and dementia. This is based on this table from the “MSD Manual” (the original version can be accessed here).

The relationship between delirium and dementia

An emerging episode of “delirium superimposed on dementia” should certainly herald an active medical investigation, initiated by a possible patient-to-be turning up in the accident and emergency or medical admissions unit of a medical hospital.

Prof Donna Fick and colleagues in my view did the very first proper seminal review of the construct of “delirium superimposed on dementia”. You can view it here from October 2002.

It might first appear that increased frequency of episodes of delirium ‘lead to’ dementia, but it is conceivable that delirium is a symptom cluster of dementia. For example, look at the symptoms associated with dementia of Lewy Body type, which can include fluctuating cognition, night problems and delirium-type episodes.

The conditions typically causing delirium (such as infection, heart attacks or strokes) are themselves linked with an increased mortality.

Also, we don’t currently know the precise ‘on/off’ switch in the brain for episodes of delirium for people with dementia - meaning that we don’t know what changes in the functioning of brain networks as someone changes from a state of dementia alone to delirium-superimposed-on-dementia. This to a large degree a mystery, not due to apathy in researching this, but overridden by a powerful sense of methodological issues in research.

That delirium and dementia are distinct conditions, although they are interrelated. Is suggested in a number of ways. Delirium has an acute/sudden onset with fluctuating symptoms, while dementia is a chronic, progressive condition with gradual cognitive decline. Delirium involves an altered level of consciousness and inattention, whereas consciousness is preserved in early dementia. Delirium is often reversible if the underlying cause (e.g. infection, medication side effect) is treated, while dementia is an irreversible neurodegenerative process. Delirium can occur in people with or without pre-existing dementia. It is referred to as "delirium superimposed on dementia" when it occurs in someone with dementia.

However, it is difficult to deny that the two conditions are interconnected. People with dementia are at higher risk of developing delirium due to their underlying brain vulnerability. Delirium is an independent risk factor for subsequently developing dementia or accelerating cognitive decline in those with existing dementia.

So while delirium is not simply a symptom of dementia, the two conditions are closely linked. Delirium can unmask an underlying dementia or potentially contribute to permanent cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration.

Recurrent episodes of delirium can increase the risk of developing dementia

A compelling report of recurrent delirium over 12 months predicting dementia: comes from Dr Sarah Richardson and Prof Daniel Davis the Delirium and Cognitive Impact in Dementia (DECIDE) study.

There is substantial evidence that recurrent episodes of delirium can increase the risk of developing dementia:

A large cohort study of 12,949 patients found that a first episode of delirium after age 65 was associated with a 31% risk of developing dementia within 5 years. The risk increased with each additional episode of delirium, with a 20% higher risk for every additional delirium episode.

Delirium has been associated with acceleration of long-term cognitive decline in individuals with and without dementia suggesting that delirium prevention strategies may reduce this risk of dementia by minimising delirium episodes.

There is substantial evidence that delirium can cause long-term cognitive impairment and increase the risk of dementia:

To determine the strength and nature of the association between delirium and incident dementia in a population of older adult patients without dementia at baseline, a retrospective cohort study using large scale hospital administrative data. The study findings suggest delirium was a strong risk factor for death and incident dementia among older adult patients. The data support a causal interpretation of the association between delirium and dementia. The clinical implications of delirium as a potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia are substantial.

Delirium is associated with long-term cognitive decline

A meta-analysis of prospective studies found that delirium is associated with long-term cognitive decline, with a moderate effect size . The association remained significant after adjusting for potential confounders like pre-existing cognitive impairment.

Population-based studies like the Vantaa 85+ study, CFAS, and CC75C found that delirium is associated with accelerated cognitive decline, even after accounting for dementia pathology. This suggests delirium contributes to cognitive impairment through additional unmeasured pathological processes beyond classic dementia pathology. The DECIDE and DELPHIC studies showed that more episodes of delirium, including community-acquired delirium, are associated with greater cognitive decline and increased risk of new dementia diagnosis at follow-up, independent of hospitalisation effects. In people aged 65 years or older, an episode of delirium was associated with a decline in cognitive scores. Greater neuronal injury during acute illness and delirium, measured by “neurofilament light chain”, has been found to be associated with greater cognitive decline.

The clinical medicine of treating delirium superimposed on dementia must be informed by a clear rationale from what we can learn from non-human animals. This is will ensure w are detecting and treating the correct phenomena. Animal models have demonstrated that triggers of acute cognitive dysfunction like systemic inflammation can exacerbate neurodegenerative processes and accelerate functional decline over longer periods. That a longitudinal study found the largest cognitive decline occurred in people with high baseline cognition who experienced delirium suggests perhaps that delirium may unmask preclinical dementia pathology.

Can delirium prevention be effective in prevention of acceleration of dementia?

The evidence indicates that delirium is not just a marker of underlying cognitive impairment, but can directly contribute to neuronal injury and cognitive decline through mechanisms that are not fully understood.

Delirium prevention and treatment may therefore help reduce the risk of dementia.

This is something we should bear in mind even after the initial diagnosis of dementia. Preventing delirium episodes is something we can attempt to do with good homecare and care in residential units such as care homes or nursing homes. Giving back hope to people is so essential in what is otherwise a desperately sad situation.

Further reading

I hope that you have found this piece useful. You can read more about the essentials of dementia and dementia care in my book here and more about the basics of delirium and delirium care here. I should like to thank Kate Swaffer, co-founder of DAI for her leadership and inspiration with my projects.

Biography

Dr Shibley Rahman is a longstanding friend and supporter of the Dementia Alliance International since its foundation and was an unpaid family carer for his mum with dementia living at home until she died in July 2022. You can follow his blog here and access his book, Essentials of Delirium: Everything You Really Need to Know for Working in Delirium Care.

Dr Rahman is the lead for the neurodelirium special interest group for the American Delirium Society, an honorary research fellow of University College London and an honorary visiting professor in the University of Liverpool. He was awarded his Ph.D. in dementia from Cambridge in 2001 and is a registered physician also a member of the Royal College of Physicians of London. He has published widely on all the frailty syndromes, especially dementia and delirium. He holds his MBA and Master of Law from London in 2012 and 2010 respectively.

Since you’re here…

We’re asking you to support our members, by donating to or partnering with our organization. With more than 55.2 million people living with dementia, our work has never been more important. Donating or partnering with us will make a difference to the lives of people with dementia: https://www.dementiaallianceinternati...

Membership of, and services provided by Dementia Alliance International is FREE, and open to anyone with a diagnosis of any type of dementia. Join DAI here: /get-support/become-a-member

Read our newsletters or regular blogs, by subscribing here: /blog

About DAI: Dementia Alliance International (DAI) is a non-profit group of people with dementia from around the world seeking to represent, support, and educate others living with the disease that it is possible to live more positively than advised with dementia. It is an organization that promotes a unified voice of strength, advocacy and support in the fight for individual autonomy, improved quality of life, and for the human and legal rights of all with dementia and their families.